The knives in your kitchen come in all sizes and shapes. Some are for dining, chopping, slicing, carving, and tearing. But which knives are made for what purpose and which are essential to have in your kitchen?

In this article, I'll look at some popular knives and discuss what each type of knife is designed for (and some unconventional uses for them).

Chinese Cleaver (Asian Cleaver)

The chef's knife is the one knife that is consistently rated as the single most essential in the kitchen. However, if I could only pick one knife to have in the kitchen, it would be a Chinese or Asian cleaver. This knife's sharp edge is thin enough and sharp enough to easily cut and mince food and at the same time strong enough to handle light cleaving jobs. The side of the blade can be used to smash garlic and ginger and the top edge san be used (with care) as a meat tenderizer. The broad blade is often used to move food from the cutting board to the stove. However, due to the overall shape and size of a Chinese Cleaver, there is not as much precision as a chef's knife. Since I have a full compliment of knives, my Chinese cleaver sits on the sidelines waiting for the day when I can only have one knife to use.

The chef's knife is the one knife that is consistently rated as the single most essential in the kitchen. However, if I could only pick one knife to have in the kitchen, it would be a Chinese or Asian cleaver. This knife's sharp edge is thin enough and sharp enough to easily cut and mince food and at the same time strong enough to handle light cleaving jobs. The side of the blade can be used to smash garlic and ginger and the top edge san be used (with care) as a meat tenderizer. The broad blade is often used to move food from the cutting board to the stove. However, due to the overall shape and size of a Chinese Cleaver, there is not as much precision as a chef's knife. Since I have a full compliment of knives, my Chinese cleaver sits on the sidelines waiting for the day when I can only have one knife to use.

Chef's Knife

The most versatile knife in the western kitchen is the chef's knife. It is used for cutting, slicing, chopping, and mincing. The curved blade allows rocking back and forth for fine chopping and mincing. Chef's knives come in blade lengths from 6 to 12 inches. The longer the knife, the more you can cut, but the more difficult it is to control. If you've got small hands (like I do), you may want to stick with the 6 to 8 in. variety. Tina uses a 6 in. while I find the 8 in. allows me to grip the knife just forward of the bolster with my forfinger and thumb without discomfort (the 6 in. is slimmer so the back of the knife digs into the side of my knuckle). If you've got one of these and a board scraper, you won't need or want to use an Asian cleaver.

The most versatile knife in the western kitchen is the chef's knife. It is used for cutting, slicing, chopping, and mincing. The curved blade allows rocking back and forth for fine chopping and mincing. Chef's knives come in blade lengths from 6 to 12 inches. The longer the knife, the more you can cut, but the more difficult it is to control. If you've got small hands (like I do), you may want to stick with the 6 to 8 in. variety. Tina uses a 6 in. while I find the 8 in. allows me to grip the knife just forward of the bolster with my forfinger and thumb without discomfort (the 6 in. is slimmer so the back of the knife digs into the side of my knuckle). If you've got one of these and a board scraper, you won't need or want to use an Asian cleaver.

Santoku

This is the Japanese equivalent of a chef's knife and has been gaining in popularity in Western kitchens. It has a broad blade and a tip that is lower than a chef's tip. Typically made thinner than a chef's knife, it does not have as much structural strength or weight, but is great at all chef's knife functions except for cutting through bone. Many brands now carry santokus, but a few have made poor design decisions (edge is almost flat, tip too low, knife too thick, etc.). The Shun Classic Santoku shown here is probably the best santoku on the market right now. Unfortunately, for left handers, it's a right handed knife (the unique D crosssection handle fits right handers).

This is the Japanese equivalent of a chef's knife and has been gaining in popularity in Western kitchens. It has a broad blade and a tip that is lower than a chef's tip. Typically made thinner than a chef's knife, it does not have as much structural strength or weight, but is great at all chef's knife functions except for cutting through bone. Many brands now carry santokus, but a few have made poor design decisions (edge is almost flat, tip too low, knife too thick, etc.). The Shun Classic Santoku shown here is probably the best santoku on the market right now. Unfortunately, for left handers, it's a right handed knife (the unique D crosssection handle fits right handers).

Paring Knife

The paring knife is great for working a blade in a small space. Paring apples, cutting fruits, butterflying shrimp, and seeding a jalapeno are just some of the tasks the paring knife is well suited for. The paring knife has a thin blade that makes it easy to manuever while cutting. The sharp tip is also useful for removing potato eyes and other such tasks. In general, a paring knife is simply a miniature chef's knife - designed with the same curves and angles but smaller. This makes switching between the chef's knife and the paring knife a natural action.

The paring knife is great for working a blade in a small space. Paring apples, cutting fruits, butterflying shrimp, and seeding a jalapeno are just some of the tasks the paring knife is well suited for. The paring knife has a thin blade that makes it easy to manuever while cutting. The sharp tip is also useful for removing potato eyes and other such tasks. In general, a paring knife is simply a miniature chef's knife - designed with the same curves and angles but smaller. This makes switching between the chef's knife and the paring knife a natural action.

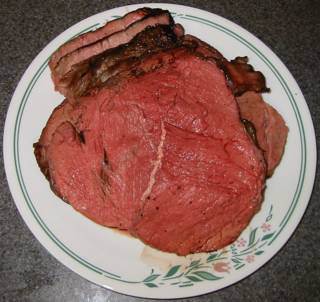

Carving Knife (Slicing Knife)

A carving knife's special purpose is to carve poultry, roasts, and hams after they have been cooked. Carvers typically have points to reach into tight places, but roast beef carvers have blunt ends. Some have hollow recesses along their blades and are referred to as granton or hollow edged or scallops. These air pockets allow for thinner slicing because they prevent meat slices from adhering to the blade. Why use a slicer instead of a chef's knife? Thickness. A carving knife is much thinner, enabling the knife to slice through finely while a thicker knife will wedge and tear the cooked meat once it cuts in too deep.

A carving knife's special purpose is to carve poultry, roasts, and hams after they have been cooked. Carvers typically have points to reach into tight places, but roast beef carvers have blunt ends. Some have hollow recesses along their blades and are referred to as granton or hollow edged or scallops. These air pockets allow for thinner slicing because they prevent meat slices from adhering to the blade. Why use a slicer instead of a chef's knife? Thickness. A carving knife is much thinner, enabling the knife to slice through finely while a thicker knife will wedge and tear the cooked meat once it cuts in too deep.

Bread Knife

A bread knife's job in life is to cut, you guessed it, bread. Many breads have a hard crust which keeps a slicer or chef's knife from digging in and gripping the bread when you start to cut. You can use the tip of the chef's knife to punch a hole where you want to cut and then slice, but what about soft breads? With soft breads, the chef's knife doesn't clip around on the crust, but while you cut into the bread, you compress it instead of slicing clean through. A bread knife solves both problems by providing large serrations that grip the crust and can saw through soft breads without squishing them. This knife is also useful for cutting dense cakes (yellow cakes, pound cakes), but use a fine serrated knife for light cakes (angel food cake).

A bread knife's job in life is to cut, you guessed it, bread. Many breads have a hard crust which keeps a slicer or chef's knife from digging in and gripping the bread when you start to cut. You can use the tip of the chef's knife to punch a hole where you want to cut and then slice, but what about soft breads? With soft breads, the chef's knife doesn't clip around on the crust, but while you cut into the bread, you compress it instead of slicing clean through. A bread knife solves both problems by providing large serrations that grip the crust and can saw through soft breads without squishing them. This knife is also useful for cutting dense cakes (yellow cakes, pound cakes), but use a fine serrated knife for light cakes (angel food cake).

Utility Knife

This knife is the in-between knife. If you've got a 4 in. paring and a 10 in. chef's, you might want a 6 in. utility knife for all those jobs in between. Sometimes it's also called a tomato knife (usually when it has medium serrations) or a sandwich knife. Since Tina uses a 6 in. chef's knife, I use that instead.

This knife is the in-between knife. If you've got a 4 in. paring and a 10 in. chef's, you might want a 6 in. utility knife for all those jobs in between. Sometimes it's also called a tomato knife (usually when it has medium serrations) or a sandwich knife. Since Tina uses a 6 in. chef's knife, I use that instead.

Boning Knife (Fillet Knife)

This thin knife allows you to remove membranes from meat and meat from bones easily. Usually, it is made thin enough for the blade to be a little flexible. Typically, this will be the sharpest knife you own because it will also be the thinnest knife. Use this to cut anything soft that needs fine precision work, but don't cut semi-frozen meat with this blade (use a chef's knife for that). The Victorinox or RH Forschner brand boning knife with Fibrox handle is probably the best boning knife available and is 1/5 the cost of most high end knives. This model goes for $10 and the handle doesn't get slippery when coated with juice and membrane from the poultry you're working on.

This thin knife allows you to remove membranes from meat and meat from bones easily. Usually, it is made thin enough for the blade to be a little flexible. Typically, this will be the sharpest knife you own because it will also be the thinnest knife. Use this to cut anything soft that needs fine precision work, but don't cut semi-frozen meat with this blade (use a chef's knife for that). The Victorinox or RH Forschner brand boning knife with Fibrox handle is probably the best boning knife available and is 1/5 the cost of most high end knives. This model goes for $10 and the handle doesn't get slippery when coated with juice and membrane from the poultry you're working on.

Meat Cleaver

This knife is used to hack pieces of meat with bone apart. Usually imprecise due to the amount of force you need to use, the meat cleaver sections meat pretty well. I suggest using a seperate cutting board because you'll probably cut into the board a bit. In western cooking, there will be very little need for this knife because most of the time we trim the meat off the bones. When quartering a chicken, a boning knife is used and we avoid cutting through bone (unless we're doing it Asian style where having slivers of bone is part of the look and feel). Most of the time the butcher handles the bone cutting for us with their rotary and band saws (which produce much cleaner cuts and a meat cleaver).

This knife is used to hack pieces of meat with bone apart. Usually imprecise due to the amount of force you need to use, the meat cleaver sections meat pretty well. I suggest using a seperate cutting board because you'll probably cut into the board a bit. In western cooking, there will be very little need for this knife because most of the time we trim the meat off the bones. When quartering a chicken, a boning knife is used and we avoid cutting through bone (unless we're doing it Asian style where having slivers of bone is part of the look and feel). Most of the time the butcher handles the bone cutting for us with their rotary and band saws (which produce much cleaner cuts and a meat cleaver).

Steak Knife (Dining Knife)

This is the knife your guests will use to tear cooked meat into bit sized chunks. It's usually best to have large pieces of cooked meat served whole to preserve the juices and have your guests cut them. A steak knife does not cut meat as much as it tears very finely.

This is the knife your guests will use to tear cooked meat into bit sized chunks. It's usually best to have large pieces of cooked meat served whole to preserve the juices and have your guests cut them. A steak knife does not cut meat as much as it tears very finely.

What to look for in knives? Here's a short list of stuff people usually tell you what to look for: - Full tang - The tang is the part of the knife blade that is embedded in the handle. It is not necessary to buy a knife where the tang goes all the way to the back (full tang). Make sure it has at least 3/4 tang though, any less and the balance might feel weird (you don't feel like you're holding the knife; it feels like your holding a handle that's holding the knife...), constant use of over the years could result in loosening of the blade from the handle, or it might just fall out if you use too much force.

- Forged - Stainless steel knifes are generally forged or stamped. Forged knives are typically more durable and are usually thicker (more structural support). I like my chef's knives to be forged and my bread knife to be stamped (because stamped is thin and cheap). You can get all forged, but it will cost more (a nice forged slicer will also be thin, but will be pricey compared to a stamped version). The forged ones are reputed to hold an edge longer as well. I'll take this opportunity to point out that some companies like J.A. Henckels have started to do a composite stamp/forge which they claim makes their knives better than plain forged. Basic metallurgy tells us that it's probably not true, but personally I like the feel of their knives and haven't had any complaints about durability or cutting ability.

- Diamond edges - Some knives advertise "never need sharpening" due to a diamond coated edge (or something like that). I would recommend against these knives because they do eventually get dull and you can't sharpen them. Same with ceramic knives - you have to send them back to the factory for sharpening.

- Serrated edges - Some knives are serrated. That's fine. Some chef's knives are serrated. That's not fine. Serrated knives cut by tearing. This is fine for some foods (breads and cakes) but not for food preparation. A sharp smooth edge works better than a serrated edge - just remember to use a slicing action instead of pushing down through the ingredient (chopping). Remember, we're cutting, not sawing.

So what's the final verdict? Here we go:

Buying 1 knife only

- Either Chinese cleaver or Santoku

Buying 2 knives

- Chef's knife (or Santoku; from now on, I'll just say Chef's knife but I mean either)

- Paring knife

Buying 3 knives

- Chef's knife

- Paring knife

- Carving knife (if you roast) OR bread knife (if you eat a lot of bread)

Buying 4 knives

- Chef's knife

- Paring knife

- Boning knife (unless you don't prepare beef, pork, poultry, or fish)

- Carving knife (if you roast) OR bread knife (if you eat a lot of bread)

How about buying a knife set? It depends. Most of the time knife sets come with one or two good knives and the rest are not so good (that's why they put it in a set). Often you're better off buying the knives individually and as you need them instead of all at one time.